THE FARMER

The City Of Meron; the center of power in the Margaran River Valley

The life of a farmer is the noblest.

"Mama!" The cry pierced Bobin's eardrums, which had ignored the previous drone of buzzing bugs drinking her labor's sweat. Her body jolted, and as the stone-headed hoe dropped from her grasp, the snake of anxiety bit her, and its metaphoric venom spread from her gut to every part of her body... much like an orgasm, yet totally not. The voice came from Bobin's youngest living child, Waban.

Waban was still too young to understand the intricacies of bushmo reproduction. Bobin wasn't actually the child's mother, but her father - but now was not the time to sit the child down and explain. That could wait for later, since there was still half of the day's light left to use.

Going into detail over Bushmo anatomy will take many pages due to its complexity and it’s gross

"WHAT?!" was the best Bobin could manage as she bent over to pick up the farming tool. She was going to need it - there was still another plot to work, another round of reta seeds to plant. Grabbing the hoe, she drove it into the ground and leaned on it, shaft creaking. "Why aren't you watching your corner?" Bobin asked as she turned her head to face Waban. But regret rushed through her body, gushing through her tear ducts.

Waban was crying. Face bruised. Front teeth missing. Nose bleeding. The beating stick she was told to use to defend the crops with was snapped in half. And now the poor child was just yelled at. "Gods! What happened to you?"

The child let forth a deluge of verbal diarrhea, none of which was comprehensible with the near-constant choking through sobs and high-pitched bitchy voice. Bobin looked over to where the child was told to stand guard. Following the common practice of using your own children to shoo away pests, her youngest was positioned on the side where the farmland touched the road that led to the Gara river that separated the western village of Meron from the city proper. The road connected to the drawbridge leading into the walled-in city, where the queen and all the other fancy bushmo lived.

The drawbridge was still open, and halted above it was a massive group of bushmo, naner-pulled carts, and chariots. They were stopped along the perimeter of Bobin’s field, and all of her older children were swinging their sticks furiously at the naners and vivers who must have broken through the fence. The beasts had already walked over the reta plots and were eating the toma crop. The diminutive vivers were being driven back by her children. But it was the naners that concerned her most - the larger pack animals could potentially kill even a full grown bushmo with a single swipe of their tails.

There are many breeds of naners. They are used as beasts of burden and food.

Bobin sprinted as fast as a bushmo's short legs could go towards the chaos. In a glance she could see that while some of the bushmo in the caravan were laughing, most were trying their best to reign in their pack beasts. But this consideration was forgotten the instant she saw one of her other children being slapped to the ground by a naner’s tail.

Another visceral reaction coursed through her body: rage. She began to scream. She reached the commotion, hoe in hand, and began to thrust at the green-scaled, long-necked beast. Striking the beast's nose with the flat of the tool as hard as she could, the blow reverberated down the naner's neck and down its tail. The beast’s two shrunken and useless forearms even flinched upwards from the force of the strike. Bobin thrusted again, but it was only after she didn't feel the anticipated thwack did she realize that the hoe had snapped in half.

She momentarily stopped screaming for a moment to catch her breath as she repositioned her hands on the remaining portion of the shaft. The injured beast bellowed a bubbly WU-ROOOOOOH in typical naner fashion, and the shouts coming from the group of bushmo included a chorus of muted NOs and STOPs. Bobin began to feel nauseous, and her ears began to ring.

The drivers of the carts cracked their whips and tugged the reins. The naners retreated back to the road. But Bobin was too preoccupied to notice anything else as she crouched over her child sprawled across the ground. It was Saikan, the second eldest of her living children; the lucky child.

Saikan was the only male bushmo to have ever been born to Bobin's family, and only one of two living within the wooden ring that protected the villages and the city. Most bushmo were hermaphrodites, but in the rare instance when a child was born to a single sex, it was taken as an omen from the Gods. Bushmo who indulged in sin were said to be more likely to birth these imperfect children. When an entire village was sinful, it was said that the Gods would punish one bushmo by giving them sterile and dimwitted children, meant to serve as warning to all others to fix their ways. The Gods may be harsh but they weren't unfair.

The White Chariot is said to bring good luck. To be born in the year of sighting it extra is extra auspicious.

But Saikan, on the other foot, was a good omen. After he came from Bobin's tummy, the Meron beat back the hill tribes, stopping the raids for a few years. The rains returned and the crops were able to grow. His birth year brought the White Chariot, a star with a long tail that flies through the heavens which, according to the tales, only comes once every seven-hundred harvests. The villagers on the West bank of the Gara River claimed that the little baby was a miracle for a few years... until the raids came back.

As a male bushmo, he was less prone to resorting to violence, and was slight of frame with nimble limbs. He was smaller than his younger hermaphroditic siblings, but he was still head-strong and bold to make up for his size. At his guard post, he would charge at pests that would scare Bobin's larger children off. Whenever his mother was distraught, Saikan would always be the first one to say or do something to comfort her. And unlike all her other children, he was the most pious. He would be the only one who would accompany his mother to visit the shrines without giving any attitude or throwing a tantrum. Now the child was cradled in his mother's arms, breathing raggedly, right arm dangling from its socket.

If you really must know, Normal, Male, and Female bushmo can be recognized easily without looking beneath their sashes

"Why is this happening to my precious little boy?" She thought as she began to sob.

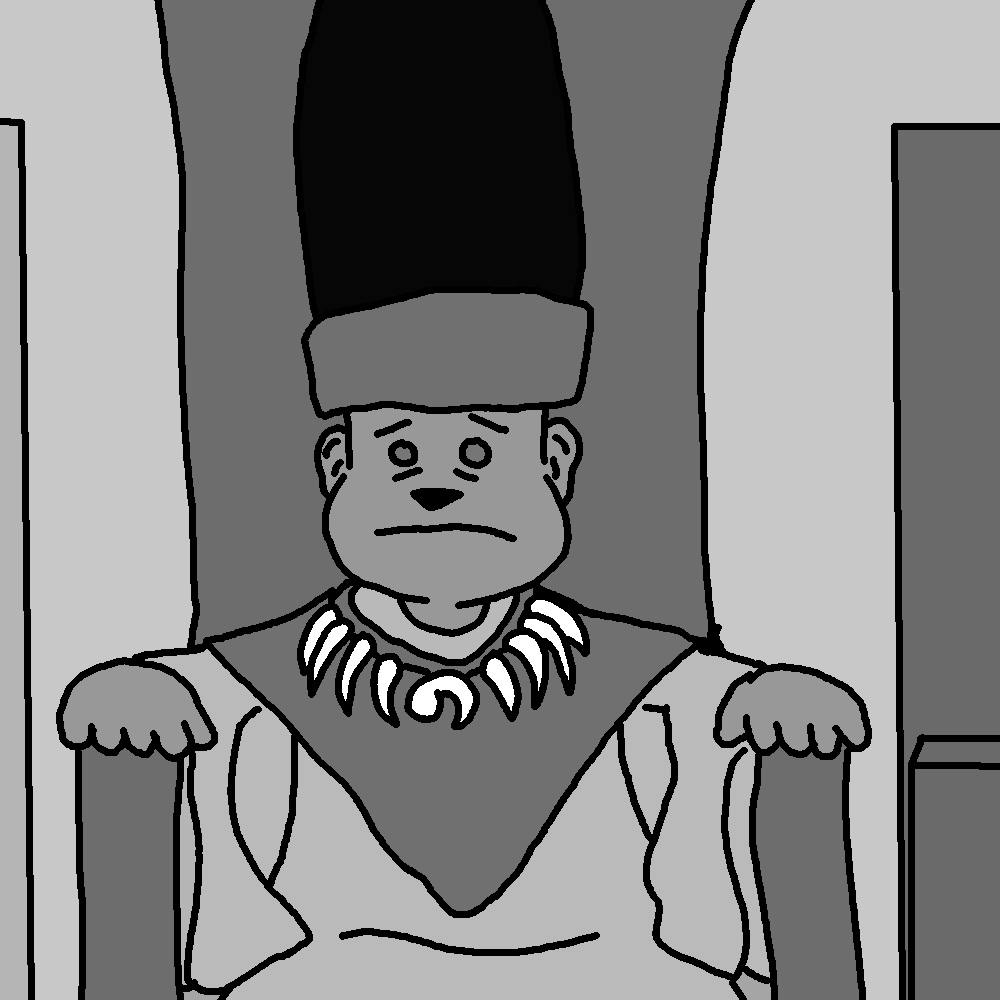

A tap on her shoulder pulled her back to the present. Crouched in front of her was a brilliantly dressed bushmo of average height, flanked by two bushmo wearing glimmering bronze helmets. In all likelihood, the bushmo in front of her was a hermaphrodite. But unlike most, this bushmo’s clothing denoted high social status. Compared to her faded red skirt and formerly beige - but now brown-stained - stomach sash, the bushmo almost glowed with symbols of wealth beyond Bobin’s wildest dreams.

This kind of wealth is never seen outside of the Walls

The bushmo crouching before her wore long lavender robes with droopy sleeves. Her exposed wrists were covered in jeweled bracelets, but her hands were lined with a number of visible scars. Hanging from her neck were two necklaces. The first one to catch Bobin’s attention was a gaudy gold chain, and from each link hung a golden pendant with a gemstone affixed to it. The second necklace was a much simpler and older in appearance. It was a greyish-yellow cord with eight long teeth which once belonged to a ferocious beast - maybe even a Mallenow - and a single polished stone in the shape of a viver. Bobin figured that just a single pendant from the first necklace would be able to fix her home and farm, and feed her family of seven a hundred times over. The stranger wore a belt made from the skin of some scaly beast that was dyed a deep red, and strapped to her left hip was a red leather sheath with etchings depicting terrible beasts.

Poking from the sheath was a sword's bronze hilt. The pommel of the sword was shaped into two swirls with a light blue gem imbedded in between. The gem was carved into a fearsome, snarling face. The handle of the sword was bound by glimmering wire, and mysterious shapes were embossed into it. Atop the bushmo's head was a tall black hat that ended in a rounded point, bordered at the brim in the same deep red as the belt. On her shins were a matching set of bronze greaves above red leather shoes, and on her chest was a bronze breastplate suspended by red cords. Both the greaves and breastplate were so finely polished that Bobin could see her own reflection. The breastplate was immaculate, lacking even the smallest scuff mark. It was rendered from three circles, like a rounded upside down triangle, each bordered with outward emanating lines, symbolizing the sun, moon, and earth.

"I'm truly sorry for what happened," were to first words Bobin heard. No longer distracted by all the shiny items and fabric, Bobin finally looked at this bushmo's face. It was a warm and empathetic face, light brown eyes almost on the verge of tears. Hard lines crisscrossed above the protruding brows, in the corners of the eyes, on the muzzle. Some were surely from age, but Bobin was sure that some of those lines were scars. The long greying hairs from the scalp protruded from the sides of the tall hat.

Based on all she knew of her life in Meron, recognition finally struck her. Wait… this must be…

To confirm her suspicions, Bobin looked at the group traveling with this bushmo. Most were warriors, wearing skirts of varying colors, barefoot, with leather or bronze helmets. Some even had breastplates. Each held a spiraling wicker shield and a javelin in the left hand, a long spear the height of a bushmo in the right, and a short blade tucked in their belt over the left hip. All of them had a red band wrapped above the elbow of their spear arm. Counting them was difficult.

A citizen soldier of Meron

Pulling on the reigns of the naners and reattaching them to the wagons were lighter-skinned bushmo, who wore simple skirts and waist bands. Though their clothing was no different from what almost everyone who lived in the villages wore - save for their yellow waist-bands their faces bore ritualistic scars. They were scars that marked them as members of the Mynar and Jork. The barbaric custom of self-mutilation was still practiced by those tribes of savages, Bobin knew. These were slaves taken during the recent conquests into the Ponosan hills, and no longer stood in the defiant way for which they were once known.

The savages of the hills will soon all be put in their place

Bobin saw the viver flock moving with the group. This breed didn’t plump like those designated for eating, but were more lithe - they had larger nostrils, sharp teeth, and were generally followed the commands of their shepherds. Bobin remembered the days she was stationed on the fence, when she saw this breed for the first time. Sentinel-vivers, the soldiers called them. They could sniff out bandits on patrols, and they chirped when they felt danger. Driving back this flock were the brown-robed viver shepherds. They were blowing their bone-whistles and lightly beating their little beasts into line with canes.

There are many breeds of vivers too

In the center of the road were the baggage and transport carts. The light carts were impossible to count, as they were still in a line extending past the drawbridge and into the city walls. Each was small enough for a single naner to pull, filled with sacks of provisions for this party. Staggered throughout the line of carts were heavier wagons with at least two naners affixed to each. These were for the warriors, who sat on low benches. On both sides of the road were light chariots, each pulled by a single spry and castrated naner. These chariots lacked decoration, and were painted in a simple red. All of them had wicker baskets; some brimmed with javelins, others with arrows.

Leading this train of baggage, wheels, and soldiers were two large chariots, each pulled by two naners. These were displays of the Meron's great skill with woodwork, famous throughout the queendom. The largest cart leading the procession flaunted intricate carvings of battle and hunt on the chassis. The rim was of solid bronze – this was a chariot fit for only bushmo of the highest social standing. Just behind was another chariot, painted in the brightest white. Its only embellishments were a crescent moon and glaring sun on the front of the chassis.

Still standing in the white chariot were three taller-than-average bushmo. One was dressed in a purely white - as far as Bobin could see – robe, with a red waist band sporting many leather pouches. The other two were in half white and half gray robes. The white-robed one was shaking a red-brown gnarled staff and yelling something. The shadows from the hood made it so that the only the reflections in her eyes were visible, giving her the appearance of having beady little eyes. Eyes aimed at Bobin and the child in her arms.

Protruding from the hood was a light skinned muzzle, lighter than most from Meron, covered in wavy blue tattoos that stretched from the visible portion of the neck and into the darkness under the hood. The size and dress of these bushmo gave away their identities as the priestesses of the Meron, the living representatives of the gods. Though biological females weren’t as rare as males, the title of priestess was only attainable by females of Meron, for reasons a mere farmer like Bobin could never fathom. Something must have caught the white robed priestess' attention, as she began to fumble over herself to get off of the chariot in haste.

Not being a complete imbecile, Bobin was able to piece together who was before her. A baggage train, chariots, warriors, priestesses of the moon and sun, city-dwellers, and a bushmo shrouded in immense wealth…. Yes, Bobin was certain of her identity.

Before her was the hand of the sun goddess, Rapa-Nui. The champion of Digeon the Water Bringer, the god who releases water down the Margaran river. The wielder of the implements made by the god Bin-Badi the Bronze Shaper. The bane of the hill tribes, the Pono, Mynar, Hyun, Jork, Falimire, and the dreaded Coh. The owner of the ancient blade Vanquisher. The benevolent ruler and re-unifier of the valley tribes, the head of the Margaran Valley Queendom. The just-handed and sure-footed. The winner of countless duels. The child of the less illustrious Maebin the Coward, and grandchild of Kabankan the Embarrassed. This was the Queen of the Meron, Fropin the Bold. Bobin felt stupid for not immediately making the connection. She worried if her wandering eyes and lack of attention to this great bushmo offended.

Kabankan was defeated in the Calemine Pass by the Coh without a single death on either side. The Meron army was forced to surrender and pass under the yolk

Maebin really wasn’t that awful, but she kept the peace her mother was forced to make after her loss to the Coh

"...Are you alright?" Fropin the Bold was now gently shaking Bobin’s shoulder.

Bobin's mouth moved to speak. She knew she had to apologize, but the words were clogged like a back logged turd. Airy-yelps were all she could manage – no words came. Fropin's face turned a shade less empathetic and her gentle grip on Bobin's shoulder stiffened. Fearing that she was only making the situation worse for herself, Bobin mustered the last of her facilities to speak.

"What about my little Saikan? What about my boy? Why did you let this happen?" She croaked, choking on the tears pouring from her eyes and dripping onto the child's face. Bobin had already lost five children. She also lost her buggy, her life partner, to raiders while protecting the fence. And now she was going to lose her little boy. She sobbed harder. Fropin's face turned to sadness witnessing such an emotional collapse, and as she looked down to the child in Bobin’s arms, she flinched.

Regardless of species, there is no such thing as a child who isn’t embarrassed by their mothers

Saikan vigorously wiped his mother's tears away with his good hand, letting out an embarrassed and yet pained, "... stop that... I'm okay." He pushed away his mother's arms, stood on his wobbly legs, and took a few steps away. A look of pain would flash across his face when the limp arm swung against his body.

"You mustn't push yourself!" She urged her son. Bobin was about to follow up with more nagging, but the obstruction of sunlight distracted her again.

Rapa-Nui speaking for the gods

The white robed priestess of Rapa-Nui towered over them all. The priestess pulled a small sack from her sash, and poured its contents - many small finger bones - onto the ground. After the bones had settled, she used the bottom of her staff and briskly etched a wavy line connecting them, closing it off in a circle. Her hood slipped off as she tilted her head back, and she began to chant. Her voice began to undulate as she reached for another sack and poured a coarse white powder into and around the circle. Her voice ended in a croak and she began to fall, head lurching forward, with eyes rolled back so that only the whites of her eyes could be seen. The two white-and-gray robes caught her at the armpits, and she drove the end of the staff into the center of the circle. Gripping and leaning on the staff, she raised both elbows as if to gesture to the white-and-greys that assistance was no longer needed. Her white eyes rolled back down to reveal piercing black eyes directed at Saikan.

Without breaking her glare, White robes pointed at Saikan, and said in a gravelly tone, "That is the child!"

Fropin looked to her, uncertain, "Are you sure?"

Her glare intensified. "This is indeed the child I dreamed of. The young child with a lame arm. The one who will bring an end to the strife with the Coh." "When was this child born?" The priestess inquired. Before Bobin could respond, she pressed on. "He was born in the year of the coming of the White Chariot, am I correct?"

"How could she have known?" Bobin thought, mouth gaping open.

"Fropin, do you require more proof?" The leader of the Meron gave an accepting nod and looked over to Bobin, who still hadn’t realized what any of this could mean.

"It appears your little 'Saikan' is the very child we've been looking for." The distinguished bushmo said to Bobin. "The mouth of Rapa-Nui had a vision in the Great Hall, showing that we would find such a child on our journey to the West. The fact that we did find the child, and so close to the city walls at that, must truly be the Gods aiding our cause."

Bobin was beginning to understand what was happening. They were going to take her sweet little Saikan away for some ritual. The realization horrified her, and there was nothing she could do. The priestesses spoke with the word of the Gods, and the Gods could not be defied without bringing calamity upon the world. The white robed priestess smiled warmly at the boy, and said, "You'll be coming with us."

Bobin wanted to scream, but she feared that would make her seem impious. All she could do was look at her little boy whose face was so stern and solemn. He walked over to Bobin and hugged her with his left arm. “He is trying to be bold for my benefit,” Bobin knew.

"The Gods need me." With that, he slowly walked toward the priestess. Shocked by such enlightened acceptance... and yet not, Bobin didn't say anything in response. She could only manage a pained and teary-eyed nod.

The white robed priestess' smile widened. If it weren't for those tattoos, it would have been an infectious smile, not the terrifying visage that it was. Her glare finally broke from Saikan and she turned to Bobin. "You've taught this child well. Do not worry. He's destined to bring fortune to the side the gods favor. I've seen visions of a chariot returning to the gates with this child, and the hill tribes, the Meron, the Coh, and all the valley brought into the fold. He will be returned here unharmed."

The hill tribes to the west of Meron have been at war with the great city for hundreds of years. Being weaker, the savages rely on hit-and-run attacks

Even with the reassurance, Bobin felt grave doubts forming in the back of her mind. "The Gods were often cruel, but haven't they bestowed enough cruelty upon my family?" she thought to herself… but thinking that way did no good either, so she restrained herself. She looked back at Saikan, his dislocated arm dangling freely. There was reason for concern when one heard the words "He will return unharmed."

Before she knew she had opened her mouth, Bobin lashed out at the priestess, crying, "But what about his arm? That is one big booboo!" She had lost two children to injuries far less serious than that. But immediately after, she felt stupid for asking such an unnecessary question.

"My sisters and I are knowledgeable in the arts of healing. Your son will be fine with us."

Bobin was resigned to this future for her son. This is what the Gods have willed. More than anything, Bobin was awash with shame that she ever felt any doubts. Who was she to question their will? It is no place for a mere mortal to deny the Gods. Fropin, standing now, took off her hat and handed it to the nearest soldier. She bowed her head and her hands fumbled at the back of her neck. Before Bobin could register what was happening, Fropin had presented two necklaces, hands outstretched.

She gestured with her chin to the one closest to her; the golden chain with nine dangling pendants - a lucky number for the Meron and their faith. Upon closer inspection, each pendant bore the image of a ship, each a different colored gem of above the craft. Bobin, only ever having seen river boats, had no idea that each of these gems was fashioned to look like a ship's sails. "This necklace is the work of the Raka, from the south of the Mar River."

The guard holding Fropin’s hat interjected. "My Queen, are you sure you're willing to give such treasure to a mere farmer? I can arrange for her to get some coppers or silvers… but gold?"

Fropin gave massive side-eye, and continued, "This is for you and your family. It's for the damages done to the crops and for the injury of your children. You can trade just one of these pendants for many services or laborers." She pulled free the nine dangly bits and handed them to the white-robed priestess, who then placed them into a pouch.

Fropin passed the pouch to the priestess, who then gave it to Bobin. The queen spoke again. "This next necklace has been in my family since before the Great Rain. You will present it to the guards at the drawbridge. They will be obliged to escort you to the Great Hall, where you'll give this to my heir, Salipin. To her, you will inquire help regarding your situation if you are in need of laborers." The queen fastened the necklace around Bobin's neck. Fropin gestured for her hat, and the guard placed it on her head. The remorseful looking guard received a strong poke to the chest from the queen, whose face had turned hard as stone.

Turning back to Bobin with a much warmer expression, she began again. "We all must get moving, towards the hills to put down the Coh menace once and for all. But before you go into town, speak with the Elder of your village, and let her know that you will be exempt from taxes for one harvest, seeing that your field is damaged... and judging by your tears, I can see you still have doubts. Before you step into the city, you should pray at the shrine and find strength in your faith." The queen was right; if Bobin was not willing to curse this whole affair, she would need to cleanse her mind of any doubts.

The Gods didn't like questions and always punished those who had too many of them.

Saikan hugged his mother and all of them headed towards the procession. The crowd of warriors had already dispersed from the field and mounted their wooden carts. Fropin and her two guards climbed onto the foremost chariot, and the priestesses and Saikan climbed onto the white chariot. The entire procession, now including Saikan, headed down the road, northwest toward the Ponosan hills. Only after the last of the train wagons disappeared into clouds of dust did Bobin turn her back, only to see ravaged fields and her five other children waiting to be told to do something. There was Helbin the eldest with her angry eyes, Neron and Tani, their usual rambunctiousness quelled to a somber calmness, little Oppona, and Waban, still crying silently. Bobin wanted to stay, take stock, and comfort her children, but she needed to attend to this list of chores.

"Helbin, watch your siblings for me. I need to speak with Maero, the village elder." The child's expression soured and she gave an inquisitive squint. "...To get help to keep guard of our farm while I go into town."

The headstrong child opened her mouth, but years of getting the switch for being disobedient kept her tongue. Bobin knew Maero's grandchildren didn't always play nicely with Helbin, but with one less pair of eyes to watch the crops for the rest of the day, the chances of a repeat incident would increase. There was no choice but to enlist Maero's large family to help. Bobin needed to change into something more pious, and she needed a gift if she was going to ask for a favor - it was the Meron way. Bobin headed toward her home. She slid into the thatched-roofed mud brick hut.

The sunlight came in through the holes and slits in the thatched roof that had long needed fixing. The light bounced off the village-provided bronze-headed spear, mounted on the wall above the sleeping leathers. Only Saikan’s and her own sheets were folded neatly. If only her other children learned to be as sweet as Saikan. Such a good chi... she averted her eyes to put it out of her mind. She donned her finest robe and knelt over the extinguished fire pit, grabbed a wooden bowl, filled it with ash, and crushed the large pieces to dust. Her second offering was ready, at least. Before stepping outside, she took the broad and shallow wicker basket hanging next to the entrance, and placed the bowl inside.

If she was going to enlist the help of Maero's family to watch over the farm, Bobin would need to bring a gift that would please the aged matriarch. She would have to bring the ripest toma fruit, a bushmo favorite, but she worried whether enough remained from the all-too-recent naner raid of the crop. She left her home and searched the field, miraculously finding nine perfectly ripe toma among the bruised, rotten, and trampled fruits. She placed them in the basket. Nine would suffice, since it was a lucky number to the Meron.

Toma fruits are a bushmo favorite

Happy with her offerings, Bobin walked through the gaping hole in the fence and headed toward the village of West Meron. She really hoped she would get back before sundown... but there was no choice, was there? Getting to the village shouldn't take any

time - this Bobin knew - as her farm was just outside the rings of huts. The shrine itself was in the center of the town. No, this didn't concern her anywhere near as much as the idea of entering the city. She had heard horror stories about the goings-on within those walls after nightfall. The city streets became a dark maze, and not all of the denizens were scrupulous abiders of the Gods' will. Just thinking about the city at night made Bobin involuntarily feel for the pouch of pendants she had tucked away into her sash.

Maero's residence, in the center of the village, towered over all the huts in the vicinity. It resembled the squared houses within the city walls, not at all like the circular huts or small inhabited by most bushmo, or the rectangular granaries. This was the home assigned by the queen of the Meron to those deemed wise and responsible enough to be the considered elder. The ground floor served primarily as an administrative office, the second as living quarters, and the basement as storage. Bobin had always marveled at the structure, thinking, "How could a bushmo ever build something so big?" Taller still was the shrine - only the top of the mound portion of it was visible over the building. She could even make out the white line of pebbles embedded on the side of the circular mound, forming a single white stripe. It was used both as the walkway to the top of the mound and as a marker of the path the White Chariot had flown on through the heavens. On the top of the mound was a pilgrim, outstretching her arms towards the heavens, performing the final stage of prayers. Bobin wasn't the only one who was praying this early in the day.

Bobin crossed the road, passing over planks suspended over the irrigation ditches. She walked between the fences of two rows of farms owned by more affluent neighbors as their barbarian slaves worked the fields. Maero's grandchildren, among many others, were playing Tag-the-Bananahead. They must have been on their noon-rest, as not a single adult was chasing after them. Bobin could name them all, and she knew their families. Like the little shit Sheman - who was Helbin's bully, and the fourth child of Pilan the Tanner. Sheman was pushing Mushan, who was only younger than Saikan by a few days. She was the child of Maekan the Potter, who herself was a child of the former Pono slave Trilmak. The other children always teased Mushan for being born with a useless left arm. The poor little bushmo was no doubt the Bananahead now, being pelted by viver droppings to a chorus of voices calling her "Bananahead." Just like always. It always amazed Bobin that no matter how cruel the Gods may be, children seemed worse.

Hopefully their own children would be born slow. Bobin felt remorseful with that thought, but just then her eyes focused on little Yoban, getting her hair brushed by her mother. Yoban was born just four harvests ago to much controversy; even though she was slow, her mother refused to put her in the river. Another harvest passed, and no bad luck befell the village. Her next child was normal, and so the perplexed villagers stopped urging the mother to drown the child.

Unbeknownst to bushmo in the ages before advances in science, it isn’t sin that decides the kinds of children you birth, but genetics, environmental factors, and epigenetics

Already upon Bobin was the building Maero called her home. This would be the first time she entered since her mate had died defending the fence just this year; merely standing under the massive building transported her back to that grief-stricken episode. But she knew Maero's family well enough that she didn't feel too much unease.

Standing next to the entrance was Big Berna, one of Maero's many children, wearing her signature white headband. A large and gruff bushmo, she held a double-handed axe with a bronze head to her chest. "What business are you here for?" she bellowed as she tightened her grip on the axe. A look of recognition flashed across her face, "Oh, it's you Bobin..." and she repeated her question again, but in a less aggressive tone.

"I'm here to ask your mother for a favor." Berna's grip relaxed, axe hand dropping to her side. The big bushmo squinted at Bobin, then down to the toma fruits in her basket, then into the doorway, and finally back at Bobin. The moment of silence felt uncomfortably long, until finally the big bushmo took two toma from the basket with her big hand and gestured with a quick head tilt that Bobin was free to enter. Only seven toma fruits... the number made her uneasy.

Stepping in through the doorway, Bobin's eyes took a moment to readjust to the darkness. No candles were lit, and only half of the windows weren't covered by curtains. “Is this a bad time?” Bobin thought to herself... but considering today’s events, would there be a good time? She took a few more steps into the structure, but there was no one in sight. Looking around, all she could see were clay pots, more clay pots, the stairs, and a few tables in the center of the room with clay pots on them. The pots were filled with grains, salt, dried fruits, reeds, naner jerky, beads, and other goods collected or made by the residents of Meron’s west village. Bobin considered continuing her search up the stairs until she spotted shaking white hairs from behind a table.

Maero was in the middle of knitting, naked save for a sash around her waist, sitting on a mat. She looked up when Bobin unintentionally blocked light coming in through the window.

The old bushmo glared with her one good eye. "Excuse me, Maero, it's me Bo..."

The old bushmo cut in with a pained expression, "I know who you are, Bobin the Daydreamer." Bobin always hated that nickname, even though it fit her perfectly. "And I see you bear toma fruits in that basket. Now what favor have you come to ask of me?" Maero was gruff and to the point, she cared little for Meron etiquette, which required the host and guest to have a winding conversation that eventually meandered to the purpose of the meeting.

This unsettled Bobin, and for fear of trying the matriarch's patience even more, she continued politely, "Yes, I have come to ask a favor from you."

The elder grimaced. "I already know that, you Bananahead! What will you ask of me?"

"I've come to request assistance in watching my farm for the rest of the day."

"You have six children for that task. And why are you leaving your farm now?" Maero looked to the floor where the sunlight shone, and then to rug she sat upon. "It is only slightly past mid-day, there is still more work you can do!"

The events of the day rolled off of her tongue. A look of empathy came to the elder's face, but as Bobin asked for assistance for defending the farm while she was to go into town, Maero peered into the basket.

"Seven? You mean to curse me with seven toma?"

Bobin replied defensively, "I came to bring your family nine toma fruits. Berna took two as I came in, so I figured..."

"BERNAAAAAA!" Maero screamed.

The big bushmo vaulted into the building, mouth stained purple from the fruit, axe swinging, face burning with intensity. The swinging axe accidentally knocked into a clay pot, knocking it down. It shattered with a loud crash, spilling grain. This visibly shocked the bushmo and she leapt sideways into more clay pots. This continued two more times, until there were no more pots within jumping range to break. The dusty ground was now covered with shattered ceramic and the contents they used to hold.

There would have been yet another extended silence if Maero hadn't been making a silent hissing noise as if she were boiling over internally. Her face twisted and reddened at her adult child, now clearly ashamed, crying silently over her bloodied feet.

Maero burst with a loud "BER...!" and caught herself, "...na. Did you take two toma fruits from Bobin?" Berna began shaking her head. "Don't lie!" The matriarch pointed sternly at her daughter and the shaking stopped suddenly and her eyes widened. Tears began to glisten in the corners of her eyes. Bobin didn't want to deal with this now, and instinctively put down the basket, reached into her robes, and produced two medallions. The glimmer of gems caught their eyes, and Maero fell silent. "Please help watch over my farm while I go into town!"

The old bushmo was flabbergasted. "How did you get hold of.... those?"

Bobin was forced to retell the same story, realizing that she had left out the details of the two necklaces the first time. She then produced the queen's old necklace from her robes. This was more than enough to convince Maero. "With gems like those, you're asking for too little…." The old bushmo trailed off, muttering about all the things Bobin could purchase with just a single medallion.

Not wanting to spend any more time here, Bobin had the last word. "Please do as you see fit for such a gift, but I need to see the Gods and do what was asked of me by the queen. I'm sorry for the intrusion."

She placed the remaining toma fruits and the two medallions on the rug Maero sat upon, and quickly stepped out of the house with her basket and bowl, jumping over all the piles of debris. Once outside, she headed to the center of the village. She could still hear Maero shouting "Berna," the sound of stumbling, and the crash of more pots breaking until she passed the first row of huts. She was off now to the village shrine to clear her mind of doubts.

Memories from her childhood flooded back when she saw the mound and its twenty-seven surrounding stones up close. The former village elder was Sawaro. She always stunk of cantano-berry wine, and she had a tendency of putting her rough hands in the sashes of other bushmo, often without their permission. She was known for her songs and old tales of their gods. Bobin remembered most of the stories.

Many of these gods are based on historical figures

The northernmost stone was aligned with Digeon the Water Bringer, who brings the rains and keeps the rivers flowing. To the south is Rakalion, the god of boats; northwest was Wakalion the Bringer of Seeds; southeast was Pagoor the Naner Mother; Bin-Badi the Bronze Shaper was next to Alamanee the Shepherd... and so on.

Bobin needed to change her appearance before the Gods before she got too close to the mound, so as to not offend them with her pride. She pulled her hood over her head and walked with a fixed bow. Stooping forward, she came to the entrance of the mound which faced the north, and Digeon. Before entering, she walked counterclockwise around the mound, rubbing each stone with ash. Only by showing all the gods favor could a bushmo hope to gain any themselves. Then, and only then, could a mere mortal enter into the den.

All towns and villages had shrines, and all shrines had their own dens. At least this is what Bobin was told; she had never seen the world outside of the ring fort surrounding the city of Meron and its tributary villages. The bushmo-dug dens were, according to legend, more ancient than the constructions above them. Among the old stories of the Gods told by Sawaro were tales of how all creation came into being, where the first bushmo came from, why the first great tribe of bushmo spanning the entire world fell from grace and fragmented, and the War of the Gods that almost destroyed everything. Every shrine made was created as a means of equally worshipping all the Gods who survived that war, so that such a cataclysmic war would never occur again. There were the main nine gods, each with their own two children - lucky for Bobin, she had enough ash for all.

Before each stone she stood, reciting the name of each God, stating her intent to give ashes in offering, and finally rubbing said ash into each stone. It wasn't the most arduous task, and having the prayers memorized made it easy, but it did take time. But Bobin found meaning in it - but that was not always the case.

Bobin remembered receiving the cane for not showing enough devotion to each and every god. It took her many years to understand the significance of it all. Really, it wasn't until the disappearance of her first child did she truly say those prayers with purpose. And since she lost her mate for life, her buggy, she visited the shrine every evening, when the moonlight was bright enough to make the White Chariot's path glow upon the mound. Always praying for rain, for the health of her children, and for the fence to hold the hill bandits at bay.

Duties almost complete, she placed her bowl and basket outside of the cave mouth and entered into the cavern. Inside was pitch-black, save for the yellow glow at the end of the tunnel. Taking twenty-seven steps, exactly on the footprints embedded in the ground she made her way to the end of tunnel. And she now stood above the shaft that would take her down into the den. The air was already musty. The glow of the torches gave her some comfort as she began to climb down a vertical shaft, down twenty-seven footholds. She recounted the tales of where these dens came from as she climbed.

According to legend, all was created by the most powerful God. The whole caboodle existed as one, and earth was a place where the lesser Gods could live among the first tribe of bushmo. But the bushmo, ignorant and self-indulgent, chose only to worship the Gods that they had a use for, and ignored the rest. Farmers prayed for good harvests, shepherds prayed for healthy flocks, pregnant bushmo prayed for strong children with the essence of both male and female. It is said that when bushmo prayed more for their own interests than for the blessings of all gods, their selfishness threw the world off balance. The spited Gods grew jealous, and battle began. The almighty God split into two halves, the Earth Mother and Heaven Father, and with this split, the war intensified.

Mountains rose to stab the skies, some belched burning stone and ash, and the heavens responded by sending icy spears and their own burning stones to the earth. During this war, the first tribe fragmented and scattered across the world. The bushmo who survived the cataclysmic war dug caverns like these, hiding until the war ended in a stalemate after thousands of years. After the war, the most pious bushmo were allowed to come back to the surface as long as they made offerings to each and every god.

The wicked bushmo were damned to live forever without ever seeing the surface again. They dug deeper, going deep within the dark realms of Molokai, becoming twisted and warped in their evil. The descendants of these bushmo are still rumored to live within the depths of the earth, in crystal cities, black ponds and rivers, and the deepest blacks of caves.

Perubin fighting the Craggmo in the dark labyrinth

Many legendary heroes spelunked the caverns, verifying these tales. They were the source of epics - tales of battling the fierce Buggmen, Bananaheads, Craggmo, Mallenow, and other mythical monsters. But many of these heroes never returned. These stories excited the imaginations of all Meron, but they only saddened Bobin.

Her first child - Bopin - knew of these tales, and idolized their heroes enough to venture through the caverns with her friends. They were never found. Bobin tried not to think about that, halfheartedly convincing herself instead that Bopin and her friends had made their way to another village's shrine. It was always a possibility – it was rumored that the tunnels in the dens were all interconnected.

She reached the bottom of the shaft. She wasn't alone; there were two other bushmo on their pilgrimage here, both lying flat on their bellies embracing the cold dirt before the stone dish in the center of the chamber. The stone dish was filled with ash and bone, indicating that they had just cremated and were about to intern the remains within the bosom of the earth mother. By burning the dead under the sky, and burying them within the ground, bushmo maintained the balance of the universe. Bobin felt an empathetic sadness for their loss, but she had to pray. She stepped around them as quietly as she could, trying not to say "excuse me." Aside from the sound of breathing, coughing, and the crackle of the torches echoing down the black chasm, the den was silent. There was no talking allowed in the embrace of the Earth Mother. Ducking under some ancient gnarled roots, Bobin found her spot before the black stone altar opposite the steps, laid down, and embraced the earth.

The Black Altar

She couldn't help but think of Saikan again. Imagining the child being used as a sacrifice, with his still-beating heart torn from his chest. She could picture an infinite number of scenarios of the little boy being hurt and succumbing to his injuries. The last Bobin would see of him would be his corpse, dressed in burial linens. Or… what if he were tied to the chariot of some dreaded Coh barbarian, used as some sort of sick trophy? But perhaps worst of all was the thought that she may never see him at all, ever again, like Bopin. Thinking of all the ways Saikan could die shook her up, and now the caverns were echoing the sounds of muffled sobs. Bobin could have sworn she heard the other pilgrims climbing out of the den, and with them, the glow of the torches grew fainter....

The sound of more scurrying woke Bobin up. Wiping drool, tears, and caked dirt from her face, she made for the exit. There were differently robed bushmo laying on the ground around her, maybe five in total. "How long was I asleep?"

Now feeling anxious that she had done an irresponsible thing, Bobin quickly climbed out of the pit. Judging by the angle of the sun, she had slept a quarter of the day away. She was going to need to hurry if she was was going to make it back to the farm to feed her children dinner before dark. She grabbed her bowl and basket and climbed up the mound along the path of the White Chariot from the West. Arms outstretched towards the heavens, she gave an honest effort in her prayer to the Heaven Father and hoped that the dirt stains and her hurriedness wouldn't offend. As she began to walk off the mound to the East, a pang of guilt struck her. "Of course the gods would notice," and she returned to the top of the hill. She didn't want to face the same fate as Arakan, the fool in the tales who didn't give each god enough prayer, and was struck by lightning. Bobin wasn't going to cheat. She had a family to care for.

The tales of Arakan are all moral lessons

Once she put in an amount of time that felt acceptable, she walked out of the circle of stones and then bolted for the road. It was late afternoon, and families would be preparing for the next day's work and cooking dinner, and there were few bushmo walking about the village. When she came within sight of her hut, she was shocked to see another group of bushmo on her farmland. As she came closer to the hut, she saw that they were her fellow villagers, and directing them all with points of a cane was Maero. The thatch was being replaced, the broken portion of fence had been repaired, and the holes in the mud-brick walls were being patched. The previously untouched soil had been tilled, and at each corner of the farm were two guards with sticks in hand. Her children were nowhere in sight, and this worried her. At the entrance gate stood Berna, face still stained with Toma juice, feet bandaged. Upon seeing Bobin running towards her, the large bushmo called for Maero.

Before Bobin could open her mouth, the old bushmo warmly interjected, "Your children are in my home, where dinner will be provi... your face! It's covered in dirt."

"I just finished praying." Maero looked to Berna expectantly, and she sprang into action. The big bushmo took off her headband and began to scrub at Bobin's face. Bobin tried to swat away Berna's hands, but she was overpowered and felt like a baby in the bushmo's embrace.

"I hope you like all the work we've put into your farm." Maero finished.

"Thank you for all of this, but I still need to go into town." Bobin replied. What amazing treatment. If it weren't for the shiny gemstones, would she have ever expected this much help?

"Of course. Berna, let her go." Bobin placed her basket and bowl back inside her home and finally headed towards the river.

At the edge of the river was half of a wooden drawbridge with two guards chatting up a storm, and under them was the Gara river; behind them were the imposing walls of Meron. The two guards looked young enough to have just been presented with the sash of adulthood within the last year. When they saw Bobin heading in their direction, they quieted down and raised their shields.

"Who goes there?" The guard on the left shouted.

"I'm Bobin of the West village."

"From in or outside the fence?"

It wasn't a question she had ever been asked before. Everyone in the Western village knew everyone else, so everyone knew who was given the more dangerous assignment of having to farm the lands outside of the ring fort. It wasn't a matter of being inside or outside, it was a matter of being lucky.

"...inside. That farm right over there is mine." Bobin pointed toward her plot.

"Why are you heading into town? And have you spoken about this to your village elder?" Bobin showed them the old necklace, and told them an abridged version of the day's events. The guards whispered to each other and looked suspiciously back at Bobin.

As she waited for a response, she looked at the ancient walls of Meron. Poking out above the walls was the Palamine hill with the wooden Great Hall standing proudly on the top, and emanating from its spire was a cloud of light smoke. The walls, the city, everything here was built and ruled over by Mero the Founder. The legends said that after defeating the Craggmo and the Cannibalistic Lithian with the great sword Vanquisher, and then battling the last of the Mallenow, Mero came to the Margaran Valley to build a home for her tribe.

There are many conflicting stories about the founding; among the favorites was Mero shouting at the Margaran river, splitting it

The evil spirits of those she had slain conspired, and brought the Great Rain which made the Margaran River overflow. Mero, ever defiant to the foes of her tribe, built the walls of Meron, shaped like a spear point. They were the strongest walls known to bushmo, and the “Spear of Meron” split the Margaran river into the Gara to the West, and Mar to the East. Mero would continue to rule for another nine-hundred ninety-nine years...

Coming back to reality, Bobin grew nervous that the guards were keeping her waiting. As she was about to ask if they were going to let her in, the guard on the left shouted to the others on the wall, "LOWER THE BRIDGE!" The guards near the giant alarm bell on the wall scurried about, some bumping heads in the process, and they began shouting to bushmo on the other side. With that, a heavy groan ruptured from the wall, and the wooden drawbridge slowly descended.

"I was told to ask for an escort to the Great Hall."

The two guards squinted at Bobin. "We're not allowed to leave our posts unless rotated. If you need an escort, ask someone inside the walls."

Walking past the two guards, Bobin looked back, worried that this would take much too long. The guards had started talking again, and the laborers were leaving her farm for the village. She looked beyond the farmlands, the village, the shrine, the carts coming up the road towards the city, and the fence that protected them all. Before her eyes were the Ponosan hills, where the queen had taken her little Saikan. She could see smoke coming from a number of small cook fires in the pass. The army must have travelled enough for the day.

It comforted Bobin that at least her child was accompanied with the citizen soldiers of Meron. The same army was used by Fropin the Bold to smash the once vast numbers of the Pono, Mynar, and Jork who harassed Meron and her allies. So many slaves came back after those battles. The other tribes of the Ponosan hills, the Hyun and Falimire, were both eradicated to the last bushmo. No, there was no need to worry; this was the most disciplined army of the entire Margaran river valley since the founding of Meron several millennia ago. No doubt would it make quick work of any of those barbarians from the hills. Prayer really did make her think more clearly. How could she have ever doubted?

The third stage of the famous battle that ended at Purmi Creek

Bobin crossed the bridge and entered into the walled city. "Where can I find someone to escort me to the Great Hall? I was told by Fropin the Bold to ask for help from Salipin." Bobin asked the eighteen guards, all wearing immaculately polished bronze helms, who manned the winches of the drawbridge. Many scoffed until they saw the necklace upon Bobin's neck. One wizened guard, who looked like a veteran of many battles – the two missing fingers from her right hand indicated enough - volunteered immediately.

Torabin, second in command at the west gate, a legend in her own right

"If this was a request made by my queen, then I will do as asked."

Incredulous, a middle-aged bushmo butted in, "You know we can't leave our posts unless we're rotated out!"

Moving to stand next to Bobin and lightly urging her to move into the city, the wrinkled guard responded, "And exceptions are made when it's at the request of the queen or the high council. This is one of those times. And do you expect for her to be able to find the path to the great hall at dusk by herself?"

Bobin and the guard pressed onward into the city. Bobin initially wanted to make small talk, but the guard was single-minded in her mission. As Bobin followed in silence on the stone-paved road, she looked at the new scenery, trying to ignore the lingering stench that hung in the air. Perhaps it was the time of day, but she felt a tinge disappointment seeing the city from within the walls for the first time. The streets were almost empty, and most signs of life came from lights glowing from the cracks in door and window frames. Aside from storehouses and granaries, all of the buildings were in the same square design of Maero's house. They were flat-roofed, and were one, two, or sometimes three stories in height. Some of these buildings seemed to be stacked on top of each other almost haphazardly. Now that she thought about it, compared to the grid that the farmland was made on, the buildings within the walls seemed to lack any order or logic in their placement at all. These buildings looked ancient and dirty, with random graffiti scratched into the walls. This wasn't this image she had in her mind of Meron.

The City Of Meron had many fires and was rebuilt each time. The original orderly lines of the city were forgotten

The road they were on was initially straight at the city’s entrance, but then there were several sharp bends, many forks, and random inclines and dips. Along the sides of these roads were narrow and shallow trenches, and once they were close enough to see clearly, Bobin realized that these were the source of the rancid stench. They passed through a street that was much wider than the other one, looking like it could serve as a bazaar. She had heard from her fellow villagers that Meron boasted a market where you could buy anything in the world, as there were bushmo from every city. Bobin herself had only seen the pole boats going up river on the Gara, but the ports were on the shaft of the “Spear of Meron,” in the South Meron village, on the other side of the river. But if this small space was the "Great Bazaar of Meron" then she was disappointed.

While most of the bushmo in the space were busy putting away their wares in the dimming light, Bobin's suspicions were confirmed. This had to be the place. One vendor had the small squared skull-hat of the Yaw-yaw, a bushmo tribe from west of the Ponosan hills, who built their entire towns into the sides of hills and were at war with the Coh.

There were a few vendors wearing silken face veils, who must have been from the East of the Domosan Mountains, who lived in Oases with reed huts and built giant triangles.

There were a few strange pants-and-head-scarf-wearing Rakan heathens, who built stone ziggurats with statues placed on top and were known as legendary mariners.

There were some of the Talima, Nira, Anakk, Ulay, Zaran, Nala, and so on. There must have been a representative of every tribe in the Margaran valley... and there definitely were others that were more alien, hailing from lands so distant Bobin wouldn’t have been able to guess. But some wore hats that curved forward, others had their backs covered in tattoos, a few wore bronze skull caps, and others wore poofy hats of fur and scale. It was strange how every culture’s silly head covers varied so wildly.

Bobin and her escort continued down the winding roads, the Great Hall coming in and out of sight. She was beginning to lose track of the number of times she was able to see the structure from the maze-like road. Soon, they reached the foot of the Palamine hill.

The road's indecisiveness ended in a marble staircase that led straight to the Hall. The two climbed up the hill, and upon reaching the top, Bobin looked in every direction. Never had she seen how big the world was. There were the Ponosan hills to the West, as well as her entire village. The Domosan hills that turned into mountains to the East, along with the Eastern village, were also contained within the defensive ring fort. And to the South was the southern Meron village, which rivaled the size of the city proper, with its own ports on both the Gara and Mar riverbanks.

Bobin was amazed by the size and apparent age of the hall before her. The wooden structure was bigger than anything Bobin would have thought possible, and the spire at the end of the building impressed her most. It looked taller up close, and she estimated that it stood at least three times taller than the squared brick buildings of the city. The wooden panels and the sloped thatched-roof had weathered into a dark grey.

Above the entranceway were two massive tusks of some long extinct beast facing upwards to the heavens and strung beneath them was a rope with a number of bleached skulls. There were so many skulls that they were piled up on each side of the entryway. Most of them were bushmo, the heads of those whom most likely either lost their duels or were enemies who fell in battle.

Dueling is a common way for aristocrats in the Margaran Valley to settle disputes

Others were of familiar beasts, with some shaped in ways that were described in nightmares and the legends of old. The smoke floating from out of the building had a sweet smell, at least compared to the stench of the city. Bobin and the guard moved aside old animal leather curtain blocking the entrance, and stepped into the dimly lit hall, hazy with smoke. The four guards inside the door stared lazily at the two of them, and they passed without a word.

The Great Hall felt much smaller inside. It was lined with unworked logs for columns, black with soot, with even more skulls tied to each one. Behind the columns and along the walls were large stone idols. It was difficult to see exactly what they were supposed to symbolize, but once the number of them counted over twenty, Bobin knew they were for each of the gods. At the end of the hall was a fire pit - the source of the smoke and sweet aroma. Bobin continued forward, and beyond the smoke she could see a number of bushmo, dressed in robes standing before three chairs and speaking in whispered tones. One chair was enormous. To the left was a simple gray chair – which may have formerly been white. And to the right of the great chair was one of the same size as the white seat, occupied by a Bushmo dressed as brilliantly as Fropin the Bold.

Bobin stopped in her tracks. She stood before a mightily powerful bushmo – for the second time today, no less – paralyzed by her nerves. But the guard continued onward without her. She really hoped that Berna did a good job of wiping the dirt from her face. The guard must have quietly announced Bobin's presence, as the seated bushmo said an audible, "Where?" and the guard spun around squinting through the haze. Seeing Bobin, she pointed her spear and beckoned her with a gruff gesture.

Her best robes lacked the color and embellishment visible on the robes these bushmo wore, and Bobin felt more self-conscious now that all eyes were on her, a simple farmer. Never had she felt more out of place. Moving her mouth to speak, the seated bushmo leapt from her seat and briskly walked over to Bobin, hand on the hilt of a sword at her belt. "Where did you find that necklace?" whispered Salipin, heir to Fropin.

"Fropin herself told me to bring it to you." Bobin was able to manage. Salipin came within strangling distance and brought both hands up to Bobin's neck. She flinched and looked up towards the vaulted ceiling of the tall spire. She closed her eyes.

"Hold her still." She felt the weight of many hands holding down her arms, and then the cold hands around her neck. Expecting the worst, Bobin took in her last breath and braced herself.

The hands moved away, and Bobin opened her eyes again. Salipin was gently placing the necklace around her own neck, and said, "Thank you for bringing this back. I can only assume there are more reasons for you being here now. Am I right?" Bobin nodded her head unintentionally to the same tempo a bell ringing distantly in the West. The sound hushed the entire hall. But the sound of more bells, this time coming from the Western city walls, drove the room into a panic.

"Looks like we'll have to wait on that. Everyone to the wall!" After the shocked Salipin gave the order, all the bushmo sprang into action and ran for the exit. Bobin did her best to keep up.

Coming out of the hall and onto the top of the Palamine hill, she looked west, where the blood-red sun on the horizon and was drowned out by thick smoke and a great fire.

Most of the guard towers of the fence were blazing, and before the background of these flames, Bobin saw the silhouettes of hundreds of bushmo running from the fence and the village, towards the city walls. Panic struck. Her children were not inside the walls.

Running down the Palamine hill with the others, Bobin saw flames building to the south. And, she realized, to the east as well. During her life, she only remembered the eight raids that required her to personally defend the fence. She remembered, as clearly as the day it happened, hitting a savage Jork charioteer with a well-placed javelin to the stomach….

But never had she seen an attack of this size. This was going to be a long and bitter fight and she'd need many more javelins. Following Salipin and her councilors down the winding rounds, the once sleepy streets came alive with bushmo running out into the open. Armed with spears, shields, bows, slings, javelins, atlatls, and baskets filled with stones, the masses were also heading towards the walls. Some of the older and more finely-dressed bushmo carried more exotic-looking weapons and wore armor of leather and bronze. Running alongside hundreds of bushmo, Bobin really hoped she wouldn't trip – she imagined herself trampled and unable to defend her children.

They reached the foot of the west wall and climbed up the stairs when the bells - first in the east, and then the south – began to ring with urgency. If the assaults on those sides were as fierce as it appeared in the west, everyone within these walls would be trapped.

"How could this be happening?!" someone randomly yelled from on top of the wall, a sentiment that in all probability everyone in Meron was thinking. Bobin reached the top of the wall and saw her worst nightmare.

A multitude of organized formations of spear and shield-holding soldiers marched to the beat of drums. They stuck to the roads between each plot of farmland. A loud commotion was erupting from the west village - shrill yelps and blood curdling screams. Around the shrine, the god stones were being toppled, and a small group of soldiers climbed up the shrine and had placed a large banner on the top of the mound. The Coh. In the distance, Bobin could see groups of unarmed bushmo with their hands up in surrender.

The poor fools, didn't they know to never surrender to the Coh? Those savages consume everyone they take.

Dispersed between the organized blocks of uniformed soldiers were smaller bands of wailing warriors covered in body paint. Anyone from Meron would have known that they were the savages from the Ponosan hill tribes.

Before all of these these formations were chariots rolling at a leisurely pace along the main road. All but one were small in size, painted a simple red, with two warriors riding on each of them. The largest chariot that rode in front, aside from a few scuff marks, was white, only adorned with symbols of a crescent moon and a glaring sun. In that chariot were two tall bushmo, one dressed for battle holding a child, and the other in a blood-stained white robe.

Running towards the river and through the farm lands were the all the villagers, farmers, children, and defeated fence guards. They were trampling Bobin's remaining crops, and all the guards posted at her farm were already on the bridge at the river bank, crying for the drawbridge to be lowered. All except one. Berna stood there defiantly; ready to face the oncoming horde.

The number of bushmo on the bridge increased with each passing moment, and so did their pleas of "LET US IN!" until they were all drowned out from the wailing, screaming, and shouting from around the walls. A child on the edge of the over-crowded bridge fell into the river and vanished, and then another, and then an adult who put up more of a show, splashing a little before disappearing into the rushing water. Through the crowd, Bobin could see Maero's head. She wanted to yell, but there was no way she would be heard.

"We can't let them in! The Coh will come in after them!" a bushmo nearby shouted.

"But if we don't, they will be eaten by those monsters!"

And then the arrows from the wall flew. Bobin froze in horror. The entire front row of bushmo on the bridge became pincushions, and many fell into the water. Maero herself was struck by several arrows, keeling over and dragging in the two children holding her hands. Another wave of arrows came and struck another row, while those behind began to running towards the incoming hordes.

Bobin was shoved violently. There was a riot erupting on the wall. Some bow-wielding bushmo were being pushed off by their sobbing fellow citizens, and a large group was abandoning the wall. Bobin looked back to the fields, where a mass of villagers were already surrendering to the savages. The large horde was halted behind a large armored bushmo in a white chariot whose hand was raised to the sky. Berna still stood her ground. A lone chariot with two skin-painted savages rolled down at full speed towards the obstinate bushmo.

A javelin throw, a quick side-step, and an axe strike to the naner's head had the two chariot riders rolling in the dust. They both stood up, dazed, and Berna thumped the flat of her axe blade on her chest, shouting. The two savages hit their shields with their swords, and they charged her. The shield of one painted bushmo was ejected from her hand with a strike from Berna’s two-handed axe. The second swing found itself embedded deep in the warrior’s neck. The other savage was upon the big bushmo at once, stabbing at her abdomen. Berna kicked the bushmo was great force, putting the warrior into the dust again.

Now bleeding from her stomach, Berna wretched the weapon from the dead warrior's body, almost popping her head clean off, save for a flap of skin that kept the head dangling. Berna and the remaining warrior parried each other's blows, until the big axe found itself in that warrior's chest. A javelin from another light chariot caught Berna in the throat.

Bobin was pushed again; another crowd was leaving the wall. Her eyes followed them to the winches where tens of bodies lay, bleeding, screaming, or dead. Above the bodies were bloodied guards trying to keep other bushmo around the drawbridge crank at bay. While Bobin loved her children, she wasn’t dumb enough to doom everyone in the city by opening the gates - if only these bushmo valued the safety of the city. Bobin followed the crowd, knowing that she would need to help fight off anyone who would try to open the gate. But by the time she reached the gate it was too late - a corpse slumped over the levers, and the drawbridge fell down with a BOOM! All the bushmo around the winch began to panic and run away. The chariots came charging down the road.

Prying a shield and spear from a fallen guard's hands, made easier because of missing fingers on the corpse, she walked out of the walls and stood on the drawbridge. She crouched behind the shield and readied her spear. If she was going to die, it wouldn't be as a coward. Bin-Badi the Bronze Shaper would give her strength.

Bobin aimed her spear. The large white chariot led the group, and holding the reins was the bushmo in bloody white robes. Bobin aimed at the midsection of the other bushmo, the one dressed in bronze armor. The big bushmo wore a blue-gemmed-swirling sword hilt hanging from her hip, held a lance in one hand and was holding small screaming child with a limp arm against her chest in the other. Saikan.

The sight of her child made Bobin flinch upwards, and she missed. The brutish warrior’s long lance caught Bobin's shield with such a great force that she was knocked into the river. The warm water filled her nose, stinging her sinuses, and blurring her vision. In the swirl of raging water she bumped into what was certainly a child’s body caught in some roots on the river bank.

"Roots!" She grabbed on for dear life and pulled her head out of the water. The chariots kept pouring into the city, arrows, stones, and javelins flew above head, and dead bushmo fell into the river and shattering on the river bank all around her. Bobin tried to pull herself up onto the narrow stony shore, but she felt a tug at her robes and skirt from in the water. Her head was submerged again, but with a few kicks, whatever pulled at her released its grip, and she took a deep breath.

But now Bobin's skirt and sash were around her ankles. Catching the water like a sail catches wind, her skirt and sash pulled her underwater again until they slipped completely off. Naked under the heavy wet robe, she still clung to the roots. She looked up and saw the painted savages running across the drawbridge, followed soon after by blocks of organized soldiers jogging casually. On the narrow river bank under the wall, the bodies of defenders fell, bones audibly crunching. One finely-dressed bushmo screamed until she hit the ground right next to Bobin. The sound of crunching bones was accompanied by the shattering of the necklace she wore. The eight sharp teeth and polished viver amulet scattered. Salipin's dead white eyes meet Bobin's, and she began to scream.

A lone soldier broke off from a block of soldiers and walked along the wall on the bank of the river. The warrior, who Bobin guessed was only a young adult, was wearing a simple iron pot-helm and a green linen cuirass. If it weren't for her slightly darker skin, the young warrior didn't look much different from a bushmo of Meron. She even walked elegantly onto the narrow and stony strip of land in a way that was unbefitting of a savage. Bobin wasn’t fooled though. They worshipped evil gods and had proclivity for eating flesh of other bushmo. Bobin and the Coh warrior stared each other in the eyes. Bobin wasn't in any position to fight back while clinging on for dear life in the water – she knew the spear and shield-wielding warrior would take advantage of this and make quick work of her if she fought back. She closed her eyes. This was going to be it.

She felt a light prod to the face and opened her eyes. The Coh warrior stood before her holding out a spear, handle first, looking at Bobin sadly. This had to be a trick; only a fool would know that these savages had no heart. They'd eat her moments after her surrender. Her children were all dead already, and soon she would be roasted above a fire pit. Better to wash up down river and let her body warn the allies in the south. The Zaran, Ulay, and Pushan tribes would avenge their Queen and liberator. They would fight for the true Gods.

She wasn't going to give these monsters the satisfaction. Bobin took a deep breath and released the root. As she fell under the water and into the darkness, she began to panic and she flailed her arms above her head. Her hands found and gripped a round and buoyant object. She pulled herself up onto the object and saw it was a round wooden shield. A big black mountain peak being struck by a bolt from the heavens was crudely painted on it. The Coh savage, now without a shield, ran along the bank reaching out with her spear handle, shouting in her savage tongue. The Coh warrior could only follow until she reached the edge of the walls, where the bank turned into a moat.

Bobin could still see the black silhouettes entering Meron from the West on the drawbridge, bodies falling and bushmo jumping from the walls. As she floated down the Gara River, she could see the South gate opening, with more hordes standing there in their formations. Fires rose from the villages and from within the city halls. Meron was lost. Nearing the edge of the fence, she heard throaty laughter. She rolled off the shield and into the water, looking at the source of the croaking. On the wooden overhang that connected large guard houses built on the banks of the Gara River were a few painted warriors stabbing at each corpse that floated by with spears. Bobin grabbed onto the shield's handle and took a deep breath, sliding under. The TONKing of the spears on the shield startled her, but she passed the bridge, and resurfaced. Climbing back onto the shield, she floated on. The world grew darker, and Meron more distant; if not for the glow of the fires and the smoke rising to the skies, it would have been no longer visible. Bobin slipped into the darkness of sleep.

She woke to the light of morning. Opening her eyes, she saw she was still on the shield, and on solid ground. Pale bodies surrounded her, and the riverbank was at her feet. A high pitched "GYAAAAH!" broke the silence, and Bobin sat up to see where the shrill noise came from. Her eyes found a child running towards a reed hut village. Each house had a small reed boat beside it, and towards the rising sun was a hill covered in palisades....

Bobin knew who these structures belonged to: the Ulay. She knew they could be counted on, and was already imagining a scenario where she was fighting in an army of Meron's Southern allies marching on to rescue everyone who hadn't been eaten already. She just hoped she would be able to convince them and felt for the pouch with medallions, only to remember that she had lost everything from under her robes in the Gara river. "Those really would have come to great use here..." she thought to herself as she drifted back to sleep.

The southern allies and territory the Meron Queendom

She woke again to hands patting up her body. The eight spear-wielding soldiers around her jumped back and screamed. They thrust their spears defensively, and the soldier closest to her yelled, "Deepest depths of Molokai! What happened here?!"

Bobin told her story.